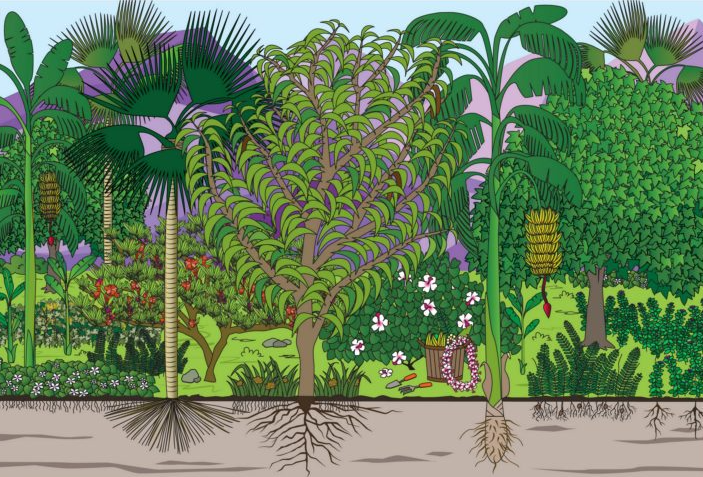

Mea kanu (plants, crops) that sustained Hawaiians for 1,500 years

Let’s imagine an ahupuaʻa – a traditional Hawaiian socio-ecological community – back in a time before Western contact. At the higher elevations, we see lush native forest surrounding groves of ʻulu, kukui, and ʻōhiʻa ‘ai. Traditional agroforestry would also allow for the growth of understory plants like ʻolena, pia, ʻawapuhi, ʻawa, and ʻape. In wet areas, cool mountain streams feed into cascading loʻi kalo (flooded agro-ecosystems for taro) and are surrounded by an expansive network of māla (gardens) comprised of ʻuala, maiʻa, kō, uhi, olonā, ‘ohe, and others.

In dry regions where moisture and soils are scarce we see a much wider variety of adaptive agricultural practices. One would commonly see kō, kī, and maiʻa growing on the kuaiwi (stone walls used in dryland systems), while uhi, ʻuala, and kalo grew within the fields. Closer to the coast stand thatched houses with home gardens providing wauke, ipu, and other non-edible plants amongst strands of niu, milo, noni, kamani, and kou.

The artwork to the left visualizes the ahupuaʻa of Waiheʻe Valley, Maui by Rina Chavez for the non-profit restoration project Wai Moku.

Although the landscapes within an ahupuaʻa would have varied depending on available resources, the cultivated plants listed above were near constant throughout the islands. Some of these important plants were already here when the first settlers arrived, but most of them were brought across the Pacific by the first people who arrived in these islands around 1,500 years ago. Those voyaging plants are known today as canoe plants. These 23 plants allowed for the development of a prosperous Hawaiian society.

The Hawaiian drug, grocery, building supply, and department stores were literally grown by their community within management systems designed to be sustained in perpetuity. This resulted in an intimate and long-standing relationship between people and plants, especially those chosen by early Polynesian voyagers to make the long journey to Hawaiʻi and sustain a new life in these islands.

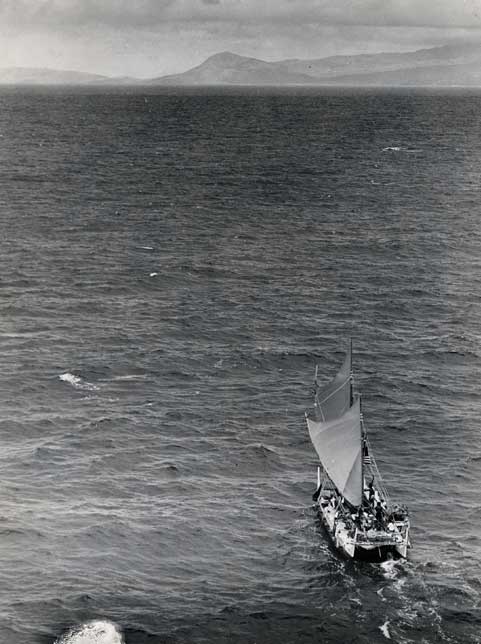

Introduction pathway: Double-hulled voyaging canoes

Polynesians brought many precious items with them on two-way voyaging journeys to Hawaiʻi: voyages that required generational wisdom, the investment of their communities, and collective perseverance. Polynesians were just one group of Pacific Islanders that intentionally migrated useful plants and animals over thousands of miles upon voyages that could take weeks to years. Although incredibly challenging, the practice of voyaging provided indigenous peoples with another layer of resiliency when living on resource-limited islands.

An important point with canoe plants and voyaging is that these Polynesian introductions took place over a lengthy period of time, as voyages to/from Hawaiʻi were long and risky. Travel by a double-hulled canoe drastically reduced the number of unintended species introductions compared to modern cargo ships, which haul thousands of tons of goods to Hawaiʻi in just a week. Although there were a handful of likely unintentional introductions over the more than 1,000 years of waʻa voyages, the rate of harmful species introductions was insignificant compared to modern rates.

I ola ʻoe, i ola mākou nei.

My life is dependent on yours; your life is dependent on mine.

The plants Polynesians stowed on their double-hulled canoes were carefully cultivated and painstakingly transported as the survival of the crew depended on it. Those onboard required food, cordage, medicine, fabric, containers, and all of life’s necessities once they made landfall. So, canoe plants represented the future sustenance of new societies and allowed for the perpetuation of genealogies and culture. Just like how the early Polynesian settlers became Native Hawaiians, these canoe plants became indigenized through a long history of fostering pilina (relationships) with these plants in the Hawaiʻi space.

Unfortunately, many endemic species in Hawaiʻi were not nutritious enough to farm and sustain communities; therefore, it was critical to develop these traveling gardens that could withstand the salty journey. In areas where marine life was sparse, canoe plants provided the additional food required on the long-distance voyages it would take to reach Hawaiʻi. Therefore, the plants aboard came from resilient lineages, much like the people stewarding the waʻa (canoe), as they both had to survive and adapt from island to island.

(Credit: edible Hawaiian Islands)

(Credit: Hawai’i Land Trust)

What is the HPWRA and why do canoe plants not have a score?

Plant Pono designations utilize the Hawaiʻi Pacific Weed Risk Assessment (HPWRA), which is a vetting process for plants that uses published scientific information to answer a set of 49 questions to determine how likely it is that an introduced plant may become an invasive species in Hawaiʻi. Technically, canoe plants were brought to these islands by humans, so they are considered non-native or introduced. But their evaluation is much more nuanced, because these plants have a history of cultivation in Hawaiʻi for nearly two millennia and host deep roots in Hawaiian culture.

Let’s review some definitions (click here)

- Invasive species are defined under federal law as (1) species that are non-native to the area (meaning, humans brought them to the place) AND (2) which are likely to cause harm to the environment, economy, or human health of that region. Both parts must be true, so even if you don’t like that uluhe in your front yard, it would not be considered invasive!

- Native plants are plants which arrived here on wind, wings, or waves, without the help of humans. Native plants are either indigenous (occur naturally in Hawai’i and other locations) or endemic (found only in Hawaiʻi).They are never given a HPWRA score, as they simply do not meet the first part of the invasive species definition. Only plants introduced by humans are screened through the HPWRA for invasiveness.

- Canoe plants are plants brought to Hawaiʻi by voyaging Hawaiians and Polynesians prior to 1778.

Most canoe plants actually score relatively safe (score <6) on the HPWRA. For a few canoe plants, namely kukui and noni, older websites (such as Weed Risk Assessments for Hawaii and Pacific Islands and Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk) may list them as high risk. Although these plants were scored when the HPWRA was first piloted over 20 years ago, many of the older assessments are still useful. Like plumeria, it scored low risk in 2002, and it’s unlikely the assessment will be updated.

In lieu of a HPWRA, we can examine the long history of canoe plants in Hawaiʻi to determine if they actually meet the second part of the invasive species definition: do they cause harm? Hundreds of years of observation indicate that the environmental harm of these species is negligible, especially in light of the unparalleled harm caused by other highly invasive plants like strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum) and Melastomes (e.g., Miconia, Tibouchina, & Melastoma genera). The main message and goal of the Plant Pono program is to reduce the importation, sale, and cultivation of invasive plants. Most non-native plants are not invasive, so we want to focus our efforts on the really invasive plants!

There is also evidence that lengthy domestication of plants can reduce the weediness of a species. For example, kukui (Aleurites moluccana) has been reported to have invasive tendencies. However, there was a wide distribution of kukui present before Western contact, providing invaluable mulch, nutrients, and animal fodder for food production. In risk evaluation, it was noticed that kukui will flourish in disturbed open habitats – which Hawaiʻi tends to have a lot of these days. But that isn’t indicative of a plant that would disrupt Hawaiian ecosystems and cause environmental harm – in fact, it is more indicative of a loss of relationship with the plant and our land as a whole. Kukui has actually been declining by 9% each decade over the last 70 years in natural areas – showing that active cultivation by humans played a key role in the proliferation of this species.

So…are canoe plants pono?

Short answer: YES! It is crucial to expand the use of native and Polynesian-introduced plant species to perpetuate the ethnobotanical and cultural identity of Hawaiʻi Nei. Hawaiʻi State laws encourage the cultivation of canoe plants in landscaping: HRS 103D-408 [Act 233 (2015)], defines “Hawaiian plants” as “any endemic or indigenous plant species growing or living in Hawaiʻi without having been brought to Hawaiʻi by humans; OR any plant species, brought to Hawaiʻi by Polynesians before European contact.”

Canoe plants were a source of community resilience before, and they can be again. We want more people to buy native and canoe plants from growers, so giving all canoe plants a Pono designation will remove any previous doubt about selling or planting these species. Want to find a canoe plant for your yard? Just tick the “canoe plant” box on your next Plant Pono search!