Summary

Learn how plant ID apps like iNaturalist and others use algorithms and machine learning to identify plants from photos, analyzing key features like flowers and leaves. This autonomous learning, paired with regional data, increases accuracy but comes with limitations. Apps may misidentify species based on incomplete data or poor-quality photos, especially for rare or native plants. In a 2023 study of plants in Hawaii, iNaturalist ranked highest for accuracy, thanks to its social networking and data contributions from users. Join the iNaturalist community to improve your plant identification skills and contribute to ecological research.

Accurate and timely identification of unfamiliar plant species plays an integral part in the early detection of spreading or newly emerging invasive weeds. After all, it’s crucial to know the species, especially when control measures are needed. A plant ID app is any app that takes a picture of a plant and returns an identification, usually within a few seconds. These apps have grown in popularity considerably in the last five years and are up to 80% accurate.

Plant ID Apps

To build a plant ID app, enormous quantities of identified photos, showing all the different parts and development stages, are fed into a neural network algorithm. The training is autonomous, with no human input or feedback. The app is not programmed to know that a yellow flower could mean the Fabaceae family or that two opposite leaves could mean the Rubiaceae family. It learns these on its own from the training photos. Some apps combine information from the photo with geography. If the app knows you are in the Pacific region, it won’t suggest a plant species from the Saharan desert. Apps that ignore geography are less reliable.

When a photo is submitted, the app uses probabilities to determine its identification output. For example, it might say there is an 85% chance the photo is one species and then list other species in the top 5 percent. The result is a list of species, which is helpful because the correct identification is not always the top suggestion. Don’t blindly trust the output of these apps, as the best way to get a correct identification is to filter through the suggestions, look at comparison photos, read descriptions, and compare them with the photo uploaded.

There are some limitations with plant ID apps. Photos of different parts of the same plant may provide different identifications, depending on whether it’s a picture of bark, flowers, or fruit. However, this can be advantageous if the first ID doesn’t make sense. The most significant limitation is that many species are missing from these apps. More than 300,000 flowering plants exist, yet the best apps can identify about 20% of these. Similar to human identifiers, these apps do best with high-quality photos. If blurry photos are taken out of a moving car, when the wind is blowing, or pictures of trees from 50 ft. away, the app won’t be able to identify it, just as humans could have trouble.

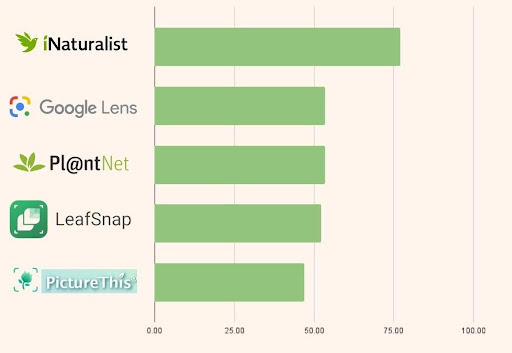

We tested their accuracy on Hawaiian Plant identifications because most apps have a Northern Hemisphere bias. In 2023, we took 250 expertly identified Hawaiian plant pictures, uploaded the same photo into the five most popular (according to the Google Play Store) apps, and recorded their accuracies. The apps were Leafsnap, Google Lens, iNaturalist, Picture This, and Pl@ntNet. (Side note: We didn’t test Seek, a product of iNaturalist. It is much less powerful than iNaturalist and is targeted towards young people.)

Ranking

First, we ranked all 250 pictures on each plant ID app. If the genus and species were correct, they got a whole point. They also got partial points of 0.6 for suggesting the correct identification as the second to fifth suggestion. Finally, they got 0.3 for the correct genus. Of course, they got zero points if they were wildly wrong. These were analyzed using a 100-point system, with 100 being the highest.

We also ranked different types of plants. We separated these 250 species into the types of plants we most often find in the wild: common native, rare native, common invasive, rare invasive, and cultivated. These were analyzed using a 50-point system, so 50 is the highest score.

Native Plants

Native is defined as a plant that arrived in Hawai‘i without human help via the wind, waves, or wings. For common natives, such as ʻōhiʻa, māmaki, and naupaka, iNaturalist received the highest score of 43 correct identifications out of 50. Rare natives (e.g., threatened and endangered plants, rarely cultivated natives, or those found in remote or more pristine habitats, etc.) were more difficult for computer vision technology to identify correctly on all apps. That’s because these plants are less likely to be encountered and uploaded into the plant ID apps. Like many of us learning to identify plants, the apps are still learning. For both of these plant types, iNaturalist was the most accurate.

Non-native Plants

For the purposes of our comparison, a non-native plant is one that arrived in Hawaii with human help, either intentionally or accidentally and moves around without human intervention. This category includes plants that are naturalized or invasive in the islands.

For common non-native plants, iNaturalist achieved a nearly perfect score, and the remaining apps had similar scores substantially worse than iNaturalist. Rare non-natives were a mixed bag; some apps identified these less common plants better than common species, something we did not expect. iNaturalist was, you guessed it, the most correct, followed closely by Pl@ntnet. Both apps scored above 80% accuracy, followed closely by Leafsnap. It makes sense that the apps identify non-native plants more accurately than natives, as most native plants are only found in Hawai’i (endemic), and there are fewer photos of these endemic species that the apps can use as training data.

Cultivated Plants

A cultivated plant is found only in gardens or places with human input. We were surprised that the apps didn’t do better for this plant type. These are plants that, in all likelihood, should be fed into the algorithm more often. They are the plants we are most likely to encounter. But again, these apps have a Northern Hemisphere bias and do not include many tropical garden plants. The apps would likely produce more accurate outputs in a garden setting on the continent. Regardless, iNaturalist scored the highest.

Results

It should come as no surprise that we highly recommend iNaturalist. It has by far the best computer vision algorithm for Hawaiian plants. The data from iNaturalist are also used by scientists for mapping native species and tracking the spread of invasive plants. Furthermore, it has computer vision technology for all organisms, such as birds, fish, bugs, etc. iNaturalist is also free and with no ads. During the course of this study, we spent way too much time on other apps watching lousy advertisements before the identification was provided, especially with Picture This and Leaf Snap. In general, those apps were slow, clunky, and often wrong.

Discussion

Social networking is one of the aspects that makes iNaturalist so much better than the rest. The observer (the person who uploaded the photo) could use the algorithm’s first suggestion and be wrong. That’s when the identifier (a volunteer who confirms or corrects identifications) guides the observer to the correct identification. Everyone gets a plant identification wrong once in a while. There is no shame in that! The iNaturalist community will chime in to help you, without embarrassment or slander, to come to the correct conclusion. Anybody can also volunteer to help identify; there’s no gatekeeping on iNaturalist; log on and add IDs to a group you’re comfortable with. If you need help, tag Kevin Faccenda, UH Botany Dept (@kevinfaccenda), or the Big Island Invasive Species Committee @biisc.

Here are some best practices for uploading observations to iNaturalist: If you don’t know what a plant is or the app is not correctly identifying it, add an ID as “plants.” That way, your pictures will be available for those of us who search for plants to identify and won’t get lumped in with birds, worms, etc. If the species is unknown to you, name the family or genus. You want to get as close as possible to get an ID from a volunteer quickly. Remember, the algorithm isn’t perfect. Check and compare the identification with other pictures and plant descriptions. Don’t upload critically endangered plants. And finally, if a plant is cultivated, mark it as such. While iNaturalist has apps in both major app stores, the website is generally easier to use, especially if you want to volunteer to help others ID their plants.

We urge you to join the iNaturalist community. Share your knowledge, become an identification superstar, and improve this program for all.

Authors include Kevin Faccenda, UH botany Department (faccenda@hawaii.edu), Chuck Chimera, Hawaii Invasive Species Council (chimera@hawaii.edu), and Molly Murphy, Big Island Invasive Species Committee (mollym3@hawaii.edu)